Dancing Around Objectification

While the context for Claude McKay’s main character in The Harlem Dancer and Ralph Ellison’s party entertainer in Invisible Man appears similar, men lusting as the women dance with deadened poise, there is a stark contrast in their situations. Both women are idealized and dehumanized, but their difference in race highlights a disparity between this idolization. The Harlem dancer is forced to relinquish her self-possession as a black woman and become the ethereal temptress to her audience. Meanwhile, the white dancer of Invisible Man is used and abused, forced to play both virgin and whore to her racially dichotomous audience.

McKay’s Harlem dancer is robbed of all agency by her viewers as they force her from the position of a performer to that of an idealized object. The dancer is objectified as her body is referred to as “perfect” before readers even have a chance to realize that her act is mainly comprised of singing (McKay 2). Her voice is described by the author as “the sound of blended flutes / blown by black players upon a picnic day” (McKay 3-4), yet the audience only notices her dancing: “devour[ing] her shape with eager, passionate gaze” (McKay 11).

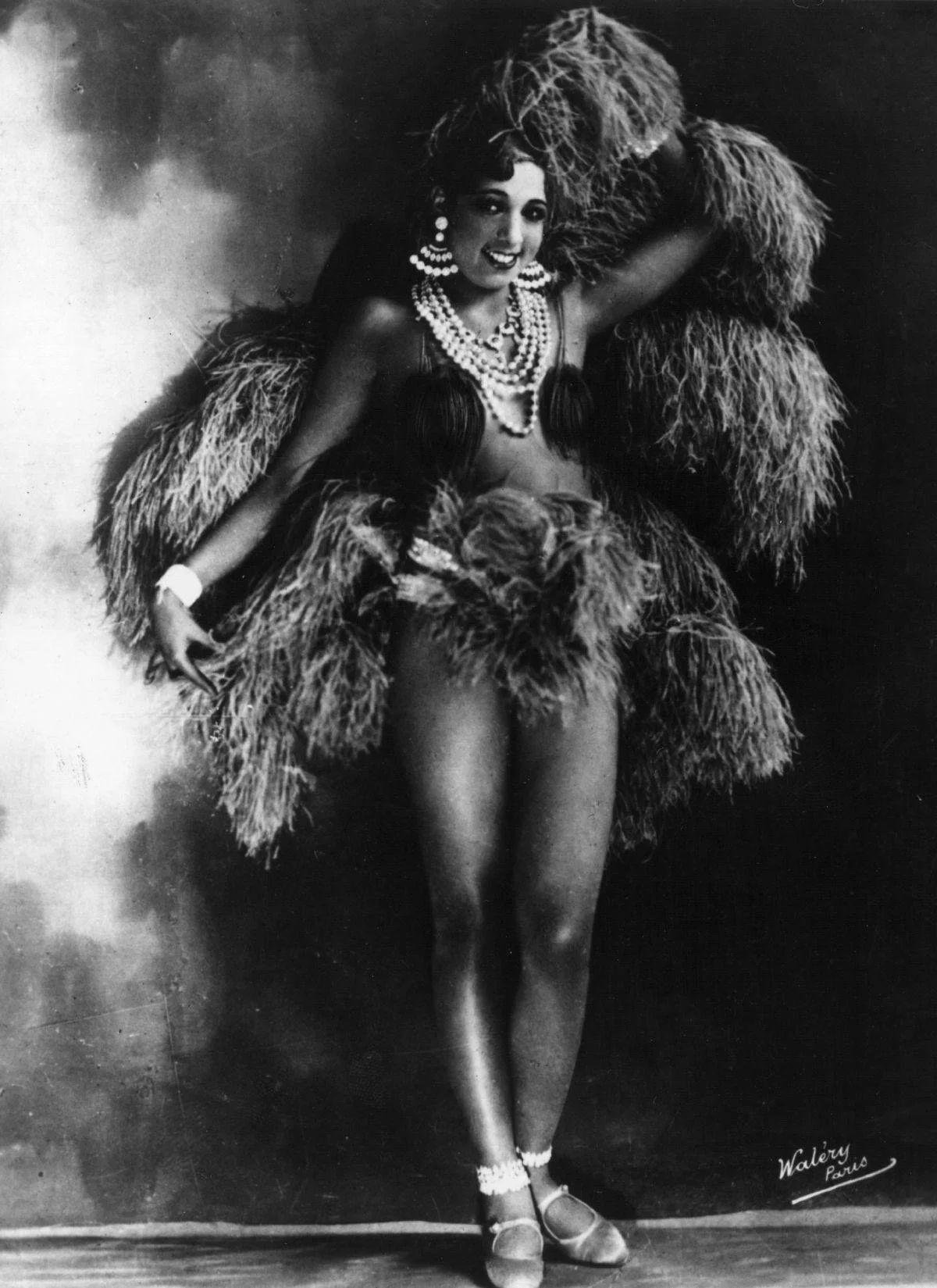

Josephine Baker – Source

The audience members are “bold-eyed” and leering. McKay notes that “even the girls” lust after the Harlem dancer (McKay 12). They are interested in what she stands for, rather than who she is, desiring her ethereal mystique, “shape,” and symbolization of sex. They want her blackness – her “swarthy neck” and “black shiny curls”– and they want it without the experiences held by the person underneath (McKay 9). Though she is denoted as a fallen angel, with the “light gauze hanging loose about her form,” (McKay 6) Harlem’s twinkling lights only reveal her “falsely-smiling face” (McKay 13) and a false self put forth in a “strange place” (McKay 14).

While the Harlem dancer experiences patronizing appreciation, Ellison’s white dancer is the center of a different storm. Black male teenagers are paraded out in front of her by the white male “big shots” she is supposed to be entertaining (Ellison 12). Placed within the gaping horror known as early to middle 20th century racism, their reactions to seeing a naked white woman might be expected, with the narrator’s reaction rising above the rest: “I felt a wave of irrational guilt and fear” (Ellison 12).

The narrator is confronted by a “sea of faces, some hostile, some amused,” yet all united under the common umbrella of white affluence (Ellison 12). Though the situation fills the narrator with fear, he longs to “caress [the dancer] and destroy her, to love her and murder her … and yet to stroke where below the small American flag tattooed upon her belly her thighs formed a capital V” (Ellison 13). The dancer is used by the white men as a conduit of shame for the black teenagers. Not similar to the Harlem dancer, it is the white dancer who takes away the autonomy and self-possession of the black audience. As the teens are forced to look upon something they can never possess, they feel fear rather than misplaced desire.

The Studio Theatre’s stage adaptation of The Invisible Man. – Source

The white dancer is used by the author to symbolize an unattainable American dream. Her stereotypical looks, including her “magnificent blonde[ness],” lily white complexion, and an American flag tattooed across her belly, position the dancer on a distant, unreachable plane from the narrator and the other black teenagers (Ellison 12). This theme is only exacerbated when the white men begin to touch her as she dances. As in The Harlem Dancer, her expression is “impersonal” (Ellison 13) and “detached” (Ellison 13). She puts on a false self in the “strange place” of the party, becoming both goddess and whore to the men, never simply a woman.

Unlike McKay’s dancer, Ellison’s dancer finds an escape. When the white audience breaks the illusion and gives chase to Ellison’s dancer, she flees with “terror and disgust in her eyes” (Ellison 13). The Harlem dancer has no say in what the audience perceives of her as a black woman, while Ellison’s white dancer is allowed a peculiar social spot: somewhere above the black teens, but below the white men. She becomes both the unattainable and the attained. While unspecified “youths” (McKay 1) of all races may gawk and admire the curves of the Harlem dancer, the white dancer comes with rules and restrictions. She may tempt, but only with black men who are forbidden to touch her. She is allowed to fend off the white men who try to fondle her like ripe fruit. All may feast upon the Harlem dancer, but at least Ellison’s dancer has the social power to deny those men “below” her status, if not those above as well.

While both women in McKay’s Harlem Dancer and Ellison’s Invisible Man are deadened by their realities, Ellison’s dancer can use her status as a privileged white woman to ultimately take back her own agency. The Harlem dancer, as a black woman, is forced to bow to the weight of her audience’s perceptions. Both works demonstrate women who are faced with sexualized and degrading treatment in America, but their contrasting portrayals augment a further issue of racial inequality.

By Victoria Merlino

Victoria Merlino is an intended English and Corporate Communication major. This paper was written for ENG 2150, taught by Professor Daniel Hengel. The paper addresses the differing means by which the female body is objectified, and how that objectification is not intersectional in terms of race, creating a space in which a white woman is allowed to regain agency where a black woman cannot.