Fomo at the MOMA: A Collective Experience

It is difficult not to be cynical in New York City’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). Commercial opportunities gleam in every corner within the sprawling property on 53rd Street: book stores, design stores, restorative cafes, and kiosks selling everything from dining ware to $500 Basquiat skateboards. With the sound of escalators humming in the background, the building has the familiar amenities of a suburban shopping mall, each floor furnished with plush seating, convenient maps and directories stating “You are Here,” and of course, ubiquitous bathrooms. MoMA is a tired tourist’s dream. Indeed, based on superficial observation, many of the museum’s visitors seem to be either sitting down wherever possible and watching strangers pass by, or taking photographs of the building’s layout itself and the visitors within it — rather than the art. So then what is the main attraction at MoMA?

In “The Museum of Modern Art as Late Capitalist Ritual,” art historians Carol Duncan and Alan Wallach argue that MoMA “addresses us not as a community of citizens but as private individuals who value only experience that can be understood in subjective terms.” Although the new MoMA building certainly does stress capital and individualism, it also paints the subjective within a collective, voyeuristic experience. Exhibits do not look out into the city skyline, as the Whitney Museum does, but fold in on themselves to tell a new story about modern art. Transparent windows look inwards into the atrium, different exhibit spaces, or the garden, where hundreds of other visitors seem to be engaging in something as interesting as the art itself. If “the museum transforms ideology in the abstract into living belief,” this introspective layout is MoMA’s newest representation of the human condition: an endeavor for pathos in an increasingly globalized, digitized world. Rather than belonging to “the age of corporate capitalism,” MoMA seems to be incorporating human psychology, and marketing to its visitors a peculiar sense of, well, belonging.

Exhibits do not look out into the city skyline, as the Whitney Museum does, but fold in on themselves to tell a new story about modern art.

This may not be obvious to the viewer from the outside of the museum. Whereas Duncan and Wallach state that the original sheer façade captured “a future of efficiency and rationality,” the new building’s opaque black glass feels just as heavy and impenetrable as the anonymous corporate offices surrounding it. The clear distinction between interior and exterior is not so much an approachable one that invites the outsider into a spiritual space, but one that underscores the museum’s exclusivity and hip factor. Congested with lounge seats and snaking lines, the dimly lit, low-ceilinged lobby feels like a cheap club that is neither efficient nor rational. The lobby is also shockingly devoid of art, the closest thing being a small collection of Robert Mapplethorpe photographs lined up to the right of the entrance under the wall text “Inbox: New Acquisitions.” Not only is the misapplication of the internet diction “inbox” an obvious attempt to be relatable and trendy, but the acquisition of the Mapplethorpe photographs within the same month as the release of the HBO documentary on his life seems all too coincidental.

Even past the admissions desk and security checkpoint, there is little sense that the space is for an art museum. The visitor is led into the Agnes Gund Garden Lobby, which is washed in a more inviting, natural light from the garden outside, but crowded with even more seats for the previously mentioned tired tourists. It seems MoMA has replaced paintings with sofas on the ground floor. Art is no longer accessible at street level as it once was for Duncan and Wallach; the visitor must make the effort to wade through the crowds and ascend into a world of elevated values towards enlightenment. Charles Baudelaire’s flâneur could not have wandered into the museum’s tucked-away exhibits from the public streets, but the Modernist, urban artist would have most likely idled in the garden chatting with other faux-bourgeois individuals.

Once visitors ultimately do trudge up the stairs to the second floor, they enter the Donald B. and Catherine C. Marron Atrium, an enormous, dark room where eight screens project Bouchra Khalili’s The Mapping Journey Project*. It is a jarring effect — coming from the anonymous, serene garden light to be hit so suddenly with contemporary politics by a Moroccan-French artist. Viewers are invited to sit once again, this time on benches in front of the screens, each telling a different, highly individualized story of the people traveling illegally due to forced migration. In light of the refugee crisis recently taking over Western media, MoMA is appealing to the sympathy of the collective using both subjective and individual experiences.

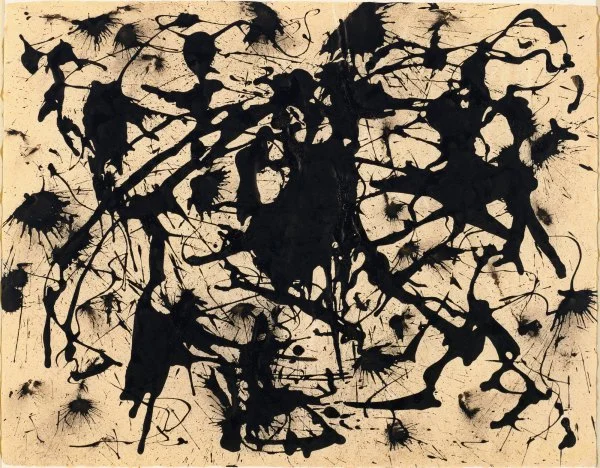

Untitled. c. 1950

Still, most of the foot traffic on the second floor is happening at the Jackson Pollock: A Collection Survey* exhibit. Its entrance does not highlight one of his paintings, but rather, a photograph of him painting using his drip technique, acknowledging that his persona is larger than his work itself and underscoring process over product, his name now a brand. One of the largest and best examples of his drip technique according to the wall text is One: Number 31, 1950, which can be seen from the other room.Since “works given special weight are framed by doorways and are often visible from several rooms away,” many of the visitors are circled around this large-scale painting and taking photographs. Some of them do not seem like they know exactly what they’re looking at or why, but even they know that this is “the mainstream of modern art history.” Cue the tourist who thinks he’s the first person to ever utter, “I could do that.” Similarly, visitors walk into the exhibit space adjacent to Pollock — Rachel Harrison’s Perth Amboy — and have no idea what they’re seeing. Also a New York-based cross-disciplinary artist, Harrison nonetheless lacks the name recognition that Pollock has. Many visitors walk into her exhibit, look confusedly at repurposed cardboard boxes, and immediately walk out.

Some of them do not seem like they know exactly what they’re looking at or why, but even they know that this is “the mainstream of modern art history.”

This ability to select what, when, and how to see, would suggest that MoMA’s layout still favors the theme of individual free choice. As if navigating the museum were like a “choose your own adventure” story, visitors can often be overheard debating which direction they will go in next. To support Duncan and Wallach’s theory, these private conversations reflect “inner experience emerg[ing] as the more real and significant part of existence.” However, these interactions can be witnessed in public, and visitors react to each others’ reactions, congregating where other strangers congregate. Call it herd mentality, but even as strangers silently pass each other going in opposite directions on the escalators, they are very much aware of the general behaviors within the museum. MoMA is no longer “implicitly denying the possibility of a shared world experience” but rather, stressing the importance of the collective. The international diversity of the artists on the third floor alone seems to suggest the importance of trying to broaden one’s perspective to a general human experience and stresses the responsibility of a global community. The third floor also boasts a balcony that overlooks the Mapping Project on the atrium and the other glass bridges that rise above it. Visitors can be seen, resting on the glass and staring out into the museum’s sleek and cavernous interior, voyeurs into each others’ introspection.

With this emphasis on an internationally aware art community, it is odd to jump back in time to the permanent collection on the fourth and fifth floor, respectively Painting and Sculpture II and Painting and Sculpture I. Unlike the original layout of MoMA, the chronology of the museum is reversed and each floor seems to increasingly harken back to what Duncan and Wallach refer to as the “iconographic program,” or what gives the contemporary international art on the second and third floor legitimacy. The kitschy From the Collection: 1960-1969 on the fourth floor depict a counterculture — Andy Warhol’s screen print of Marilyn Monroe, shiny jaguars, and music shattering the sacred silence — that has become part of the canon of high art, whereas the fifth floor’s permanent collection is hung in a traditional gallery style. When experienced from bottom to top, the museum is no longer a path towards “increasing dematerialization and transcendence of mundane experience,” but one towards a more conservative approach to art. On the one hand, the layout’s initial focus on international and American culture is moving away from the Eurocentric perspective of modern art first championed at MoMA by its first curator of painting and sculpture, Alfred Barr. Yet, this could also be seen as a taming of the supposed core of Modern Art as the most uninteresting and static part of the museum.

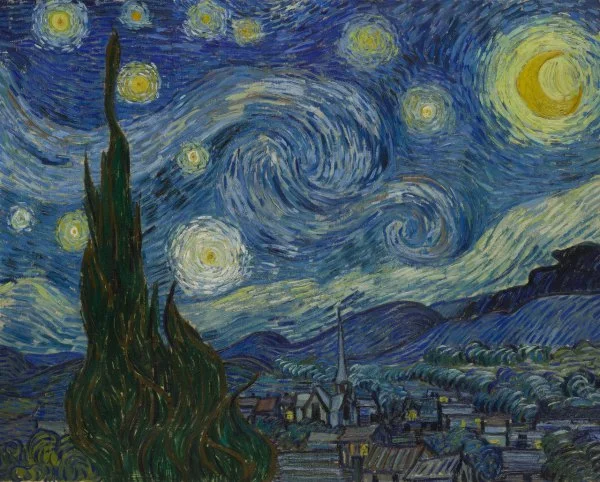

Granted, the question visitors seem to be asking the guards the most is still, “Where is Starry Night?” or “Which floor is the Degas exhibit?” In many ways, the permanent collection is still installed so that they represent movements within the traditional narrative of modernism. Duncan and Wallach note that “according to MoMA, the history of modern art begins with Cezanne, who confronts you at the entrance to the permanent collection” and follows a chainlike prescribed route of Cubism, Futurism, etc. until it makes it way towards Abstract Expressionism as the ultimate expression of the “sublime.” This white Eurocentric perspective, of course, fails to credit Asian and African art as an influence on Modern Art.

The Starry Night. c. 1889

Although Van Gogh’s Starry Night and Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon are still given precedent by being framed by doorways and being visible from other rooms, this prescribed central history with subsidiary offshoots has gotten much more complicated. Not only does the visitor work through the permanent collection beginning with Abstract Expressionism, but the new layout stresses individual freedom of choice by opening up its floor plan. Instead of a winding closed route leading towards the culmination of the iconographic program, the rooms open into each other in a non-chronological fashion. These movements and accounts bleed into each other, resulting in a less linear narrative of modernism that does not preach “aesthetic detachment” as the “ultimate value in artistic experience.”

These movements and accounts bleed into each other, resulting in a less linear narrative of modernism that does not preach “aesthetic detachment” as the “ultimate value in artistic experience.”

The way the exhibits fold in an open-plan around the atrium, although admittedly still reminiscent of a crowded shopping mall or club, reflects a reinterpretation of modern art as more than an expression of capitalistic individualism. The transparency of the architecture and prevalence of voyeurism within the museum’s walls might stoke the anxiety of urban anomie, but it also seeks to quell this anxiety through the art’s effort to create a collective consciousness. Here, like its international visitors, the museum’s multiple narratives and art movements watch each other, have conversations, and collide into something new. Pollock leads into a room full of cardboard boxes. Cezanne has a face-off with Warhol. Degas lays way to a room packed with palm trees. The art at the Museum of Modern Art may not always agree or admit to being right, and it might even have to fight to get attention, but then again, perhaps conflict is the true human condition.

By Sarah Park

Sarah Park was an English Major and Art History Minor at Baruch. She wrote “FOMO at MoMA” for ART 3282: Museums and Gallery Studies with Professor Karen Shelby. Thanks to this class, Sarah is a huge fan of institutional critique. She dreams of one day becoming a museum tour guide where she can point out the rampant white privilege and social elitism in the arts.

Quotes source: Duncan, Carol and Alan Wallach. “The Museum of Modern Art as Late Capitalist Ritual: An Iconographic Analysis,” Grasping the World, edited by Donald Preziosi and Claire Farago. Ashgate Pub Ltd, 2004.

*Editor’s Note: The exhibits mentioned in this piece have passed. Jackson Pollock: A Collection Survey ran from November 22, 2015 to May 1, 2016. The Mapping Journey Project ran from April 9 to October 10,2016.