The Subversion of Gender Roles in Macbeth

William Shakespeare’s story of Macbeth is about a war hero, mesmerized by prophecies and delusions of grandeur, who seeks power and stability in a sea of blood. The play challenges traditional gender norms surrounding masculinity and femininity with the two anti-protagonists, Macbeth and Lady Macbeth, who both leverage their power and gender to shape their relationship. The emotional oscillation between the desire for power and the guilt that stems from it affects the Macbeths’ relationship, fueling the ongoing battle for dominance.

““Go pronounce his present death,/And with his former title greet Macbeth”/”I’ll see it done.”/”What he hath lost noble Macbeth hath won.” – Act I, Scene II”

Shakespeare sets the dichotomous nature of the play in Act I with the use of rhyming couplets, alternating viewpoints, and rhetoric. One of the most famous lines in Scene One is the chiastic statement of “Fair is foul, and foul is fair” (I. i. 12), which embodies the deceptive nature of the characters’ actions. By Scene Two, Macbeth’s “brave” battle achievements are compared to “the merciless Macdonwald” (I. ii. 11). Macdonwald is portrayed as merciless and a rebel, while Macbeth fits the archetype of the courageous, yet modest, war hero. Notably, the sergeant compares fortune to the likes of a “rebel’s whore” (I. ii. 17), equivocating the seduction of wealth with the feminine. With this interpretation, Macbeth, embodying the masculine ideal, has vanquished fortune, the feminine. Duncan, upon hearing this news, refers to Macbeth as a “valiant cousin” and “worthy gentlemen” (I. ii. 26). The most important dialogue throughout the entire play takes place in Scene Three when the witches tell the prophecy that transforms Macbeth and the play altogether. After hailing Macbeth, the three witches declare him the Thane of Glamis, Thane of Cawdor, and imply he shall be king hereafter. Curious about Banquo’s future, Macbeth learns that Banquo shall be “Lesser than Macbeth, and greater./ Not so happy, yet much happier” (I. iii. 68-69). This dialogue is a critical turning point in the play, creating the parallel between desire and guilt, causing Macbeth anxiety as his desire for power increases.

Shakespeare disrupts the notions of femininity with the play’s female cast. The first physical description of the witches portrays them as masculine, withered, and wild with Banquo going so far as to say, “You should be women,/ And yet your beards forbid me to interpret/ That you are so” (I. iii. 47-49). When a letter enclosing the details of the prophecy and Macbeth’s newly received title as Thane of Cawdor arrives, Lady Macbeth worries Macbeth “is too full o’ the milk of human kindness” (I. v. 17) and will not do what’s necessary to seize the power placed before him. The prevalent trope in literature of the doubtful and worrisome woman and the power-hungry man is flipped with the Macbeths. The gender discrepancy becomes apparent when Lady Macbeth calls upon spirits to “unsex me here,/ And fill me, from the crown to the toe, top-full/ Of direst cruelty! Make thick my blood,/ Stop up the access and passage to remorse” (I. v. 48-51). Shakespeare continues to portray a disparity between the masculine and feminine as he alters the hierarchy of control. Although this was Macbeth’s prophecy, Lady Macbeth is taking the action to fulfill it.

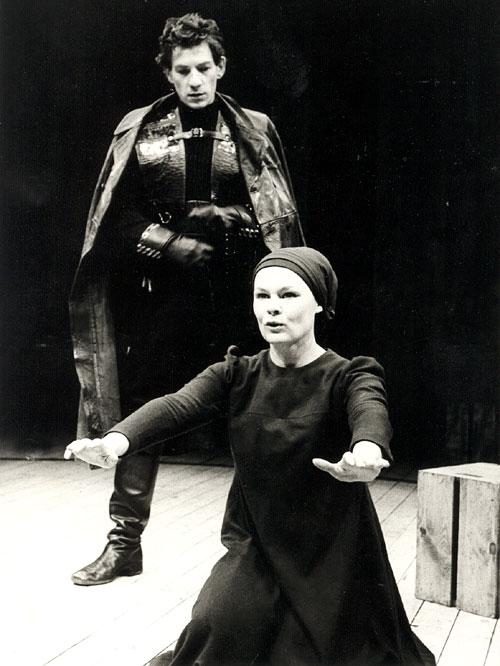

Lady Macbeth takes control after Macbeth murders King Duncan, at Lady Macbeth’s urging. – Source

Cleanth Brooks’s The Naked Babe and the Cloak of Manliness examines clothing as a symbol, specifically Macbeth’s cloak representing his own manliness. Brooks references a later scene where Macbeth’s ascent to power is described: “now does he feel his title/ Hang loose about him, like a giant’s robe/ Upon a dwarfish thief” (V. ii. 23-25). The scene implies Macbeth is not fit for these garments or the position of power he has acquired, aligning with Shakespeare’s views on masculinity. Macbeth appears “dwarfish” and ignoble in loose-fitting clothes, which are characteristics not associated with masculinity. As Macbeth struggles to follow through with the murder of Duncan, Lady Macbeth pokes at his insecurities to coax him to the task. She calls him a coward and questions his masculinity, asking him, “Art thou afeard/ To be the same in thine own act and valour/ As thou art in desire?” (I. vii. 43-45). Emphasizing her lust for power, Lady Macbeth even claims she would smash a baby’s brains out, butchering any notion of maternal affection a woman would unconditionally wield. The overturning of gender roles is mediated by the tension between desire and guilt.

Sir Ian McKellen and Dame Judi Dench in the 1978 Royal Shakespeare production of Macbeth – Source

Maynard Mack, in “The Many Faces of Macbeth,” examines the dichotomy and parallels of the two Macbeths. One of the most important contrasts between the two characters occurs in the reaction to Duncan’s death: “Their difference of response at this point is striking — not only because he is shaken to the core and cannot conceal it, whereas she shows an iron discipline throughout, but also because his imagination continues as in the past to be attuned to a world of experience that is closed to her.” Immediately after murdering Duncan, Macbeth begins to regress to a heightened state of paranoia. It is here Shakespeare introduces the earliest link between desire and guilt. Macbeth claims to have heard voices crying, “‘Sleep no more!’ to all the house:/ ‘Glamis hath murder’d sleep, and therefore Cawdor/ Shall sleep no more: Macbeth shall sleep no more'” (II. ii. 41-43) because Duncan was murdered in his sleep. Macbeth is distraught by his actions, meanwhile Lady Macbeth insists that all Macbeth do is put these thoughts away: “These deeds must not be thought/ After these ways; so, it will make us mad” (II. ii. 34). With a literal interpretation, Shakespeare foreshadows Macbeth’s demise from overthinking and madness. Mack also compares the two Macbeths to Adam and Eve. Respective to each gender, Macbeth weighs his actions more closely, even though he was tempted, while Lady Macbeth is conscious of her decisions and remains deliberate in her pursuit of power.

Shakespeare provides the final distinction between Macbeth and Lady Macbeth in the final act. While sleepwalking during the night, Lady Macbeth’s guilty conscious manifests itself into imaginary spots of blood on her hands, recalling the crimes committed. Lady Macbeth, who started out as methodical, swift in her actions, and relentless in her cruelty, becomes suicidal due to her inability to reconcile her desire and guilt. On the contrary, Macbeth has gone from being weak and anxious to vile and nefarious. Upon hearing the cries of women, Macbeth states, “I have almost forgot the taste of fears: / The time has been, my senses would have cool’d / To hear a night-shriek…” (V. v. 9-11). Even upon the news of his wife’s death, Macbeth responds with emotionless words as he is too focused with the preeminent battle at hand.

The exchange of gender and power between the Macbeths shatters the social norms of masculinity and femininity that still exist today. Shakespeare explores how power can corrupt those who were once revered and can sway the actions of both man and woman. In what could be the most accurate summary of Macbeth and human nature, Shakespeare reminds us that “fair is foul, and foul is fair.”

By Denny Jacob

My name is Denny Jacob and I am a Public Affairs major expected to graduate in Spring 2017. I wrote this essay for ENG 3005: Introduction to Literary Study for Professor John Brenkman. I chose to examine gender as I felt it was the ultimate determinant of the story’s direction, in regards to other aspects such as power, desire, guilt, and witchcraft.

FEMININITY GENDER FLUIDITY GENDER ROLES IAN MCKELLEN JUDI DENCH LADY MACBETH MACBETH MASCULINITY MICHAEL FASSBENDER PATRICK STEWARTPOWER SHAKESPEARE SOCIETAL NORMS