Under My Thumb

“I like your shirt. Do you actually listen to the Rolling Stones or do you just like the design?” he inquired.

“I listen to them.”

“Well, what’s your favorite song?” he grilled.

“’Monkey Man,’” I answered with lightning speed.

“That’s a great choice. I don’t know many girls-- especially girls in our grade—that know about that song,” he complemented. After a slight awkward pause, I muttered an obligatory, “Thanks,” and smiled half-heartedly.

“Monkey Man” was not and is not my favorite Rolling Stones song, “Gimme Shelter” is, but I feared that it was too obvious of a choice. So instead, I lied. That guy wasn’t one of the “cool kids;” I didn’t want to be friends with him and I definitely didn’t have a crush on him. Regardless, my eighth grade self still felt compelled to alter my truth.

But why?

Surely, eighth graders are notoriously insecure and dishonest creatures, but in this case, raging hormones and prepubescent anxiety were not the motive behind my duplicity. No, this stemmed from something deeper, something that has taken me almost ten years to first recognize:

I didn’t care if he liked me; I just wanted to be acknowledged as an equal.

Women who love music have to fight harder than men do in order to convince people (including other women) that our musical taste or opinions are informed and have substantial value. On countless occasions throughout my experience studying music and going to shows and festivals, I’ve been talked down to, explained to, questioned, and patronized over my musical knowledge and have witnessed or experienced unsolicited sexual advances and hostility. I’ve realized that as much as I love and embrace the music scene, the music scene doesn’t always seem to love or embrace me. And while I’ve never explicitly been told, “You are not welcome here,” I’ve also never explicitly been told, “You are welcome here.”

As a student of Baruch’s Management of Musical Enterprises (MME) major program, I’ve spent hours learning about Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Handel, Chopin, Debussy, John Cage, Steve Reich and so many more. It seems easy to recall all of those composers; their names roll off my tongue. But, what about female musicians? I’m not saying I’ve never learned about female musicians in college-- I have. I’ve learned about Robert Schumann’s musically prolific wife Clara Schumann and Mozart’s virtuosic sister Nannerl Mozart. In my jazz class, we spent a little time talking about Nina Simone and Billie Holiday, and currently in my capstone class, we are spending a generous amount of time on Madonna. However, those are the exceptions I can remember. To be fair, I know that if I look back at my old notebooks, I would find a few more examples.

Maybe my inability to quickly recall more female musicians I’ve studied reflects my abilities as a student. But even if this is true (which I don’t believe it is), there’s no way to deny the acute visual absence of women on my syllabi. And that’s exactly my point: In almost all of my musical studies, women are left out or mentioned only in relation to their male counterparts, as if they are footnotes or supplementary material.

There are two claims academics and professors usually make in defense of the lack of female representation in music. I firmly reject both of them.

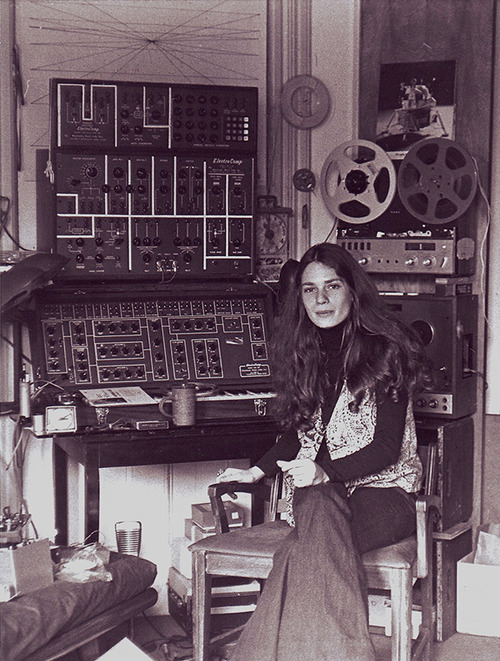

This first claim is that “Historically women weren’t allowed to be musicians, so therefore there are less female musicians to talk about.” If that hasty generalization and circular reasoning were fully true, then why do we cover important 20th century musicians like John Cage, Steve Reich and Philip Glass, but omit Laurie Spiegel? Never heard of her? That’s ok; most people haven’t. Laurie Spiegel is a highly influential figure of twentieth and twenty-first century music, and is considered to be one of the pioneers of electronic music. In the book Pink Noises: Women on Electronic Music and Sound, Tara Rodgers wrote: “Spiegel has worked at the cutting edge of electronic and computer music over many years. She pioneered modes of composition that enabled improvising with computers, as well the creation of dynamic and interactive instruments.” Rodgers also argued that Spiegel is responsible for “what we now take for granted– the archetypal figure of the electronic musician as hunched over a laptop onstage or in a bedroom studio.” Additionally, Spiegel’s “Harmonices Mundi,” based off Johannes Kepler’s idea of music from planetary rotation, was included on the Golden Record; a compilation of music that was launched into space on NASA’s Voyager 1 space probe in 1977. I was taught about Laurie Spiegel in one (that’s right, just one) class.

Well-intentioned professors usually make the second claim: “There just isn’t enough time in the semester to cover everything,” they say with great remorse. I refuse to accept that answer too. In all honesty, I would accept “I don’t have the time to rework the curriculum” or “I don’t know enough about that topic.” Hell, I would even accept the answer “I don’t want to” before “There isn’t enough time in the semester.” Here’s why: I’ve learned about John Cage’s 4’33’’, a piece of music that is quite literally, 4 minutes and 33 seconds of silence, in six different classes. Which means I’ve spent a total of 27 minutes and 18 seconds of class time listening to “silence.” That doesn’t even include the time after spent on class discussion. To be clear, I think John Cage is one of the most important musical thinkers and innovators of the twentieth century and his 4’33’’ is a work of genius. But that’s still six professors that made a conscious choice to collectively spend 27 minutes and 18 seconds of their very limited time, having their students listen to “silence”-- a “silence” so important, it is chosen over any other 20th century musical contribution. And you know what? If 4’33’’ were deemed more important than any other 20th century piece, I still wouldn’t care. But here’s the catch: we always find time to cover other important 20th century pieces and composers-- just not the ones that happen to be made by women.

“We’ve been standing here for over an hour. Would it be ok if we stood in front of you, so we can see?” I said softy in the least bitchy sounding way I could.

“Oh wow, I’m so sorry. I was just trying to get closer to the stage. Of course, go ahead,” he replied as he immediately moved behind me.

The two young teen girls next to me smiled and mouthed me an inaudible “Thank you.” “Well, that was easy,” I thought to myself a little surprised.

And then—

I felt someone touch my butt.

“It couldn’t be him, he was too nice,” I assured myself. The concert started. I boiled over in excitement.

And then—

It happened again.

“It’s really crowded. It was probably an accident,” I thought as I felt his warm breath on the back of my neck.

And then—

It happened again, but this time it wasn’t his hand. I tried to readjust; he mimicked my movements, chasing the spot in between my two butt cheeks.

“It’s my fault. I shouldn’t have moved. It probably sent the wrong message.”

I tried to stand still; he inched closer, pressing himself against me. My ears warmed with embarrassment. I turned around to face him, shook my head and raised my pointer finger, moving it left to right, signaling a clear NO. “I hope that wasn’t too forward,” I thought.

“God, you don’t have to be such a FUCKING BITCH!” he barked

Taken aback, but not shocked I told him, “I’m not being a bitch,” and swiftly turned around. For the rest of the show I was tense, waiting for it to happen again. But luckily it didn’t…

--This time.

Concerts and festivals are the places where I feel the freest. They give me the license to be comfortable in my authentic self. There is nothing else in the world that achieves that for me. However a lot of times, shows and festivals can also be unsafe places for women.

One survey had found that more than 90% of women have experienced sexual harassment at music events. Recently at this year’s first weekend of Coachella, one of the country’s largest music festivals, Vera Papisova, a reporter with Teen Vogue interviewed 54 different women at Coachella about their experience with sexual assault and harassment. Of the 54 women who she interviewed, all of 54 claimed to have been sexually harassed at Coachella just this year. To make matters worse, Papisova said she was also sexually harassed 22 times during the ten hours she spent at Coachella reporting on that exact issue. These are just the statistics that are reported and probably don’t even come close to reflecting the actual severity of the issue. In addition, Papisova writes:

“In January, Pollstar announced that Coachella continues to be the highest-grossing music festival in the world. In 2017, it grossed a record-setting $114,593,000. Sexual assault is known to be prevalent at music events, but like most music festivals, Coachella doesn't seem to provide sexual-assault literature for the people attending. When I search the Coachella website for "sexual assault," there are zero results — and that includes the FAQ section. Furthermore, every year ticket buyers receive a wristband box, and according to several attendees, this year's box had a pamphlet about the festival, which contained no information about how to get help if you are sexually assaulted.”

Why aren’t festivals like Coachella making policy changes to help? After the rise of shootings at music festivals, many events companies have taken sweeping measures to ensure festivalgoers’ safety. Some festivals have even gone as far as only allowing clear backpacks. Last year Sweden’s largest music festival, Bårvalla made the bold decision not to return in 2018 after it was reported that 4 rapes and 23 sexual assaults had occurred over the weekend. But is this what it takes for more festivals to take actions to protect all festivalgoers’ safety? Why is it that festivals take preventative measures for violence, but not sexual assault? There’s one last glaring issue I haven’t addressed:

I’m part of the problem.

I don’t listen to and support enough female artists, and I judge, vet and patronize other women’s music taste and opinions. I am a part of the equation that is perpetuating toxic masculinity in music culture. And while some people might say it’s not fair to put the burden on myself, I know that if I truly want change, it’s going to have to come from me and other women. This piece was not written out of resentment or anger; but instead out of optimism for the future. Despite never being explicitly told, “We are welcome”, women have shown up anyway and are more active in the music scene and industry now than ever before. We are gaining the power to make change. We are using the power to try and make change. Now, history just has to catch up.

By Chelsea Booth

Illustrations done in collaboration with the New Media Artspace at Baruch College. The New Media Artspace is a teaching exhibition space in the Department of Fine and Performing Arts at Baruch College, CUNY. Housed in the Newman Library, the New Media Artspace showcases curated experimental media and interdisciplinary artworks by international artists, students, alumni, and faculty. Special thanks to docent Maya Hilbert a for creating artwork for this piece.

Check the New Media Artspace out at http://www.newmediartspace.info/