WAP: Wigs, Actors and Plays

“Switch my wig, make him feel like he cheating.” This is one of the lyrics from Cardi B and Megan Thee Stallion’s explicitly sex-positive song, “WAP.” An unapologetically explicit music video accompanies this song, with the opening scene taking audiences to a CGI mansion. We’re shown a stone statue of two women back-to-back, with their tongues sticking out and water shooting out of their bare chests. The rest of the music video features the two rappers alongside a handful of other women with several costume changes, all scantily clad. One could argue that being openly sexually liberated is a recent development in Western culture, the keyword here being “openly.” This does not mean that no one was sexually liberated in the past, it just means previously there were more obstacles and consequences attached. An apt pairing to explore this idea of sexual liberation over the years is Eliza Haywood’s 1725 story titled Fantomina. It follows the tale of an unnamed female character who gives herself four separate identities to pursue the man who took her virginity. Despite the two works being published 295 years apart, Fantomina and the song “WAP” have much in common. Both pieces characterize women as individuals with sexual agency, but the most crucial factor to highlight is that the pursuit of a lover is performative at the core. Relationships demand that one puts on a disguise to be the most desirable partner.

While the song “WAP” has garnered widespread attention for its sexual lyricism and exuberant choreography, one can imagine that the initial reception of Fantomina also roused scandalous intrigue. As a character, the unnamed protagonist embodies the curiosity of a sheltered woman who still retains her virtue, also known as her virginity. She meets the charming handsome Beauplaisir at a theater. The name Beauplaisir alone suggests the immediate emphasis on the visual importance of this encounter, as beau and plaisir in French translates to handsome and pleasure respectively. Moreover, even the location of their meeting, a place designated for art and performance, sets a precedent of what is to come in this relationship. From the moment she approaches him, she pretends to be someone else. Under this alternative identity, she “dresses herself as near as she should in the fashion of those women who make sale of their favours...” She parrots the prostitutes she has seen in the playhouse, and this becomes her first disguise under the name Fantomina.

Fantomina starts as a virgin, which stirs up excitement for Beauplaisir. Even though she is the one who approaches him, when his direct advances are realized by her, she starts to back away. “He was bold; — he was resolute: She fearful, — confus[e]d, shock[e]d.” The words used here are extreme oppositions: bold versus fearful, resolute versus shocked, but either way, they are reactions. To briefly shift the spotlight onto Beauplaisir, his acquisition of Fantomina is also performative. He believes she is a prostitute, so he harbors the idea that she is playing the ingenue. In acknowledgement of this, he becomes the hungry predator who catches her “in the present burning eagerness of desire.”

Beauplaisir taking Fantomina’s virginity means that his work is essentially finished. The narrator of the story says, “now she had nothing left to give…” By this era’s standards, Fantomina has lost her virtue, so that leads her to create the identity of Celia. Celia is a humble maid from the country who follows Beauplaisir during his move to Bath. There, the same sequence of events is repeated. Celia runs into the man, she plays coy, this turns him on, he goes after her, a night of passion occurs, and he grows tired of her. Two occurrences with Beauplaisir, one as Fantomina and one as Celia, solidifies the theory that concealment and performance is the basis of their relationship.

The protagonist’s third disguise as Mrs. Bloomer, a recent widow who meets Beauplaisir purely by coincidence as she is “lost” on her way back to London, turns awry after a clandestine meeting at a hotel. The blatant awareness of her actions revealreveals that, unlike other women during this time period, she recognizesalizes her sexual agency and will go to great lengths to receive a satisfactory reaction to her performance. However, this does not stop Mrs. Bloomer AKA Celia AKA Fantomina AKA the unnamed protagonist, it only increases her determination since “she had the power of putting on almost what face she pleas[e]d, and knew so exactly how to form her behavior to the character she represented, that all the comedians at both playhouses are infinitely short of her performances: she, could vary her very glances…”

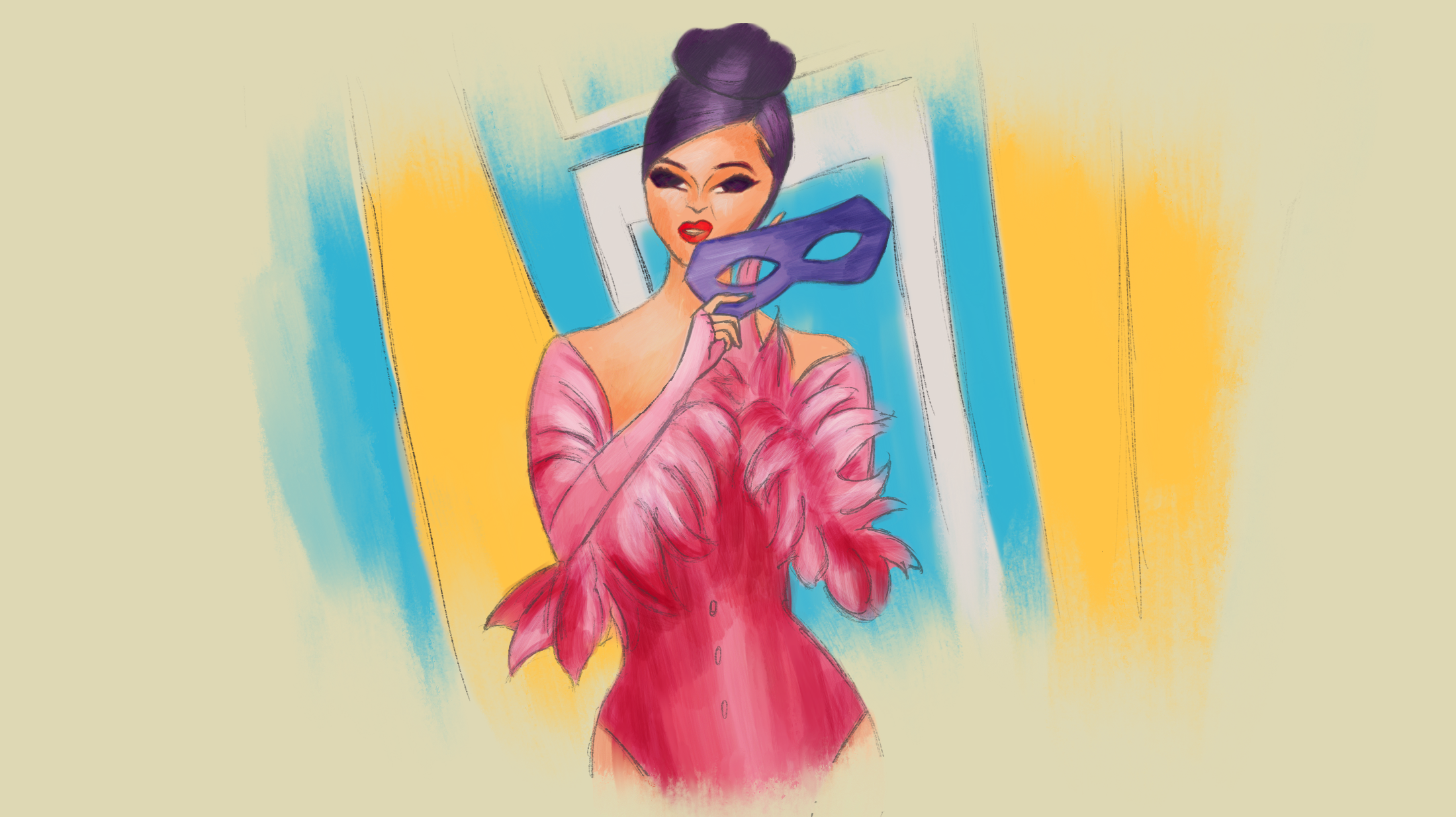

The next episode in the saga shows Mrs. Bloomer turning into Incognita. The name, Incognita comes from the Italian word incognito, which in turn comes from the Latin incognitus. The first syllable in- can mean not (ex: not dependent), while cognitus roughly means to know. In the creation of Incognita, there is now a literal concealment of identity as she puts on a mask to meet Beauplaisir. By placing this screen between the two lovers, she is stripping away her identity, allowing the “all-conquering” man to reduce her into a blank canvas. The most compelling performances are often ones in which the actor lets go of all their outside doubts, worries, and frustrations, and gives only to the audience. In this case, Incognita is a culmination of the other identities pleated over one another. Yet , at the same time, the mask is an utter disassociation that allows her to fully embody only being Incognita.

The whirlwind romance only ends when another performance is added, yet this performance requires the most labor, as the protagonist actually goes into labor and gives birth to Beauplaisir’s child. The existence of an offspring abruptly puts an end to this vicious cycle. This means that the multiple iterations of the protagonist’s disguises do not end with Incognita, they end with her being a mother, which in itself is a mutative collaboration of the identity.

To define performance as a standalone entity—, not just under the pretense of sex—, performance is work, and work requires labor. What often gets overlooked are the portions of labor that are not seen by another. This notion causes labor to be split into two parts: visible and invisible. In the scope of the invisible versus invisible labor, the performances of Fantomina, Celia, Mrs. Bloomer, and Incognita reveal how much work is necessary to maintain her love affair with Beauplaisir. Each time the protagonist puts on a new disguise, she isreiterating past versions of herself. The performative aspect of their relationship becomes apparent each time she assembles varying costumes while resembling an appealing, seductive lover. It is an unending cycle of building and rebuilding, as .the relationship itself is unsustainable without them. This pervasive need for performance is also continuously reinforced through our public personas and social media accounts.

Just as Beauplaisir thinks he is cheating, the elusive protagonist just switches their wig. Another line in the song “WAP” is, “Let's role play, I'll wear a disguise.” So, in Fantomina and Cardi B and Megan Thee Stallion’s song, both highlight that pursuing a relationship or performing a sexual act, are in fact just that: performances.

The roles we play are indeed all about WAP: wigs, actors, and plays.

Illustrations were done in collaboration with the New Media Artspace at Baruch College. The New Media Artspace is a teaching exhibition space in the Department of Fine and Performing Arts at Baruch College, CUNY. Housed in the Newman Library, the New Media Artspace showcases curated experimental media and interdisciplinary artworks by international artists, students, alumni, and faculty. Special thanks to docent Milli Encarnacion for creating artwork for this piece.

Check the New Media Artspace out at http://www.newmediartspace.info/