A Modest Proposition

By Andrew Waterhouse

New York City has been called the greatest city in the world. It is vibrant and energetic; it is a place of opportunity; it is culturally diverse; it is the leader in art, fashion, food, and theater. It stimulates all the senses. It is also dirty.

A recent study sought to rate America’s dirtiest cities. The study, conducted by BusyBee Cleaning & Janitor Services, combined data from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, the American Housing Survey, and the U.S. Census Bureau. The study determined that New York wins—by a lot. New York scored a dirtiness index of 427.9, more than one hundred points above second place, Los Angeles.

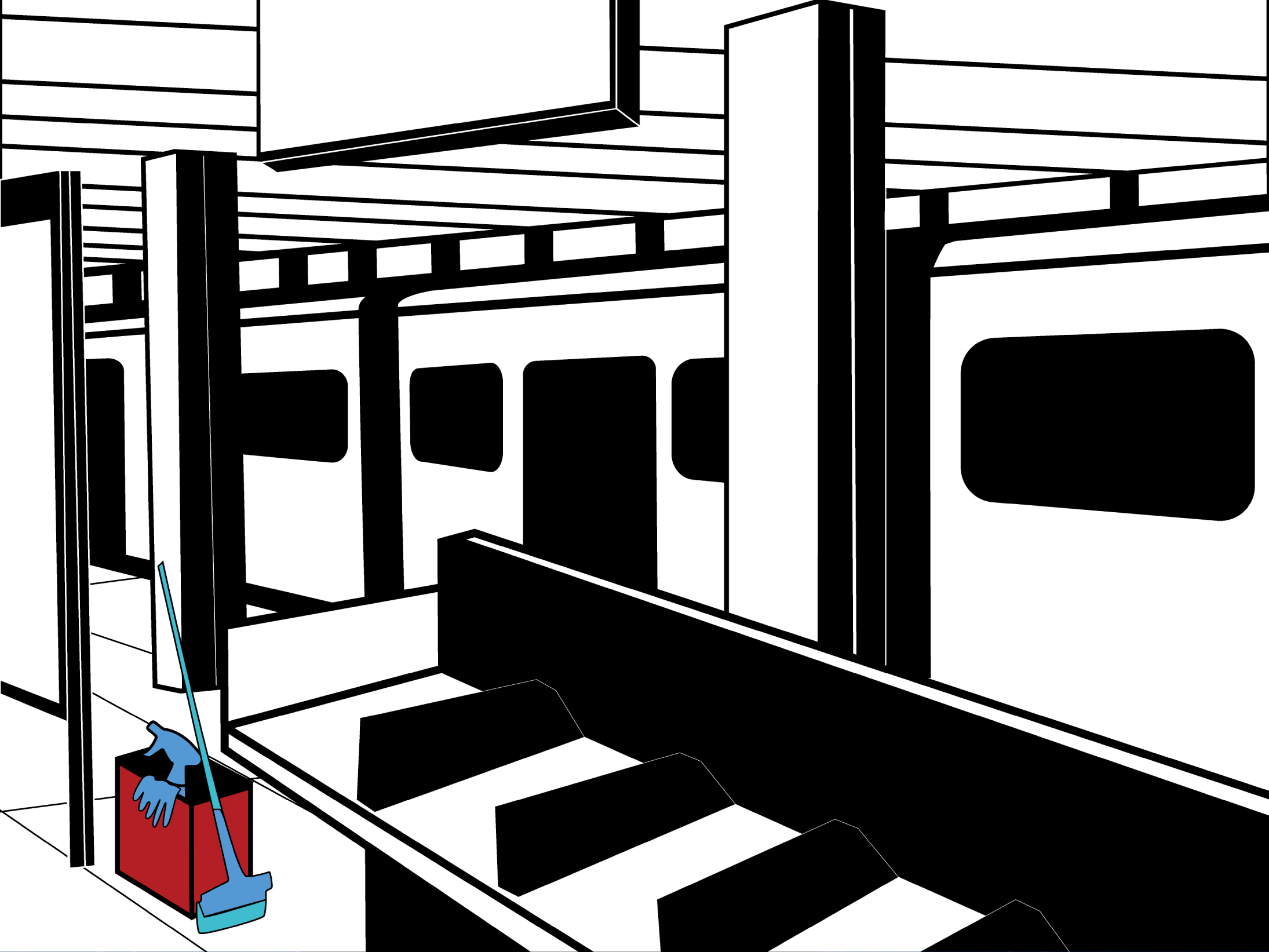

Perhaps nowhere is New York’s filth more apparent than in its famous subway system. Over 3.2 million New Yorkers are shuttled back and forth over six hundred miles of track every day—which pales in comparison to the number of germs and viruses shuttled back and forth over the same stretch. Grime and grit are caked on every imaginable surface. Urine, waste, and other fluids stain every sight. There is a thickness and dinginess to it. Some refer to the crazy, human characters who ride as “subway creatures.” One wonders what subway creatures are lurking in the filth, perhaps arising to life spontaneously from the underground soup.

What can be done about such conditions? One of the most obvious suggestions a person might suggest is to simply hire more MTA workers to clean. The problem with this suggestion is the difficulty in identifying where the MTA would find the funds for these new salaries. The subway fare would have to go up, which begs another big question: Could the fare be increased enough to hire new MTA cleaners, yet remain reasonably low enough to keep New Yorkers riding? Not likely, given the state of grunge and the number of cleaners that would be needed to make any sort of impact.

However, there is one important question to consider that can help resolve this issue: When was the last time the subways were cleanest? Actually, in the not-too-distant past. In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic began overtaking the world. The spread of the virus seemed to start slowly in some distant place; then, almost overnight, it spread everywhere, bringing large communities—like New York City—to their knees. While most businesses suspended in-person operations and workers went completely remote, some workers were deemed mandatory—such as hospital workers, grocery store workers, and so on. How would these essential workers get to and from their essential jobs? Mostly, the subway. How would they stay safe? Something unprecedented took place: the MTA shut down service during the middle of the night, from 1:00–5:00 a.m., to clean the stations and trains. It was the first time the subway had been shut down in 115 years, or since it began operating (Goldbaum 2020). Each night, an effort was made to ensure that every in-use train was cleaned and disinfected. While the shutdown of the subway system was unfamiliar, so was the newfound sparkling cleanliness—the subways were cleaner than they had ever been.

What lessons can be learned from this once-in-a-generation global event? First, the filth is not so permanent that the subway surfaces cannot be scrubbed clean. Second, horrendous as the filth is, some are willing to perform this dirty job—and in the middle of the night! Third, after the first night or two of a more thorough, deep clean, the task of maintaining that level of cleanliness becomes less daunting.

There is still a more important lesson to be learned here, which forms the basis of my modest proposition: It takes a dangerous virus and a global pandemic to wake the city to its own filth.

I have been assured by the most reputable people online that COVID-19 was planned and created by scientists at the direction of the government. These experts, who are often unfairly slandered as “conspiracy theorists,” said perhaps it was all a plan to reset the economy or to keep overpopulation in check. But by far, the best by-product was the cleaner subways.

Thus, my proposal: scientists should continue to create new kinds of viruses and periodically release them into the world—particularly into the dirtiest cities, consulting the dirtiness index report mentioned earlier. This will ultimately result in cleaner subways—and cleaner cities—at long last!

If done systematically and with careful thought, even more than subway surfaces can be cleaned. What about a virus that spreads only through dog waste? Our sidewalks will be cleaner than ever. What about a virus that rapidly replicates in large heaps of trash? Again, our sidewalks will be cleaner than ever—with the added benefit of eliminating the rank smells that emanate from them. Not to mention that eliminating trash piles will also reduce rats and other vermin who spread awful diseases! Even noise pollution could be addressed. What about a virus that only travels through the air via sound waves? Honking will be criminalized, as will jackhammering, emergency vehicle sirens, and so on. It is conceivable how these plans, carefully executed, could bring peace and quiet to our neighborhoods and great cleanliness to the best cities in the world.

There are other benefits of releasing a new, manufactured virus every year. First, in the realm of science:

It should do wonders for the advancement of scientific discovery. If scientists must fine-tune the exact biological makeup of each virus with the goal of a systematic cleaning of every nook and cranny in the cities, it will test their knowledge. It is when science is pushed to its limit that the most exciting and innovative advancements are made.

In addition, as scientists solve these complex biological feats, society’s trust in science will deepen. Those who doubt scientists' work and motives will surely come around when they see them generating innovative viruses in a lab!

As young ones observe the all-important work that scientists will be doing to keep our city clean, they will be all the more motivated to study the sciences and, perhaps, pursue it as a career.

This proposal is as much a gift to the city as it is to science!

A second benefit would be that as viral pandemics increase, the human population decreases. This leads to a host of favorable circumstances:

With fewer people around, things that become dirty are much more likely to stay clean longer.

As the human population decreases, apartments become available, rent prices decrease due to low demand, and the unhoused can find suitable places to live, which eases the burden on everyone. Thus, the major problem of affordable and accessible housing can be solved with a simple pandemic!

Cities like New York are notorious for their parking and traffic issues, again resulting from overpopulation. Imagine a city with hardly any traffic; a city with more parking spaces than could ever be filled.

As evident, this proposal is as much for cleanliness as it is for other big city problems!

There is not a single valid objection that could be made against this proposition. Some may try with preposterous questions such as, “What about everyone’s health and well-being?” What about it? Is the pollution of the city not detrimental to our health and well-being too? Critics may argue, “Is it practical to shut everything down on such a frequent basis?” Well, is it practical to live in this mess? Either of the above or similar objections are the arguments of dimwitted individuals who have trouble seeing the big picture. These are likely the ones who contribute most to the city’s filth.

With a clean, modestly populated city, New York City could finally begin to prosper. Indeed, almost every major problem within the best city in the world would be eliminated with a regular regiment of deadly viruses!

FALL 2024

Bibliography

Illustrations were done in collaboration with the New Media Artspace at Baruch College. The New Media Artspace is a teaching exhibition space in the Department of Fine and Performing Arts at Baruch College. Housed in the Newman Library, the New Media Artspace showcases curated experimental media and interdisciplinary artworks by international artists, students, alumni, and faculty. Special thanks to docent Anika Rios for creating artwork for this piece.

Visit the New Media Artspace at http://www.newmediartspace.info/