No Silver Bullet

Simon Carrillo Fernandez was 31.

Mercedes Flores was 26. She studied literature at Valencia Community College.

Luis Vielma was 22. She worked at Universal Studios.

Their lives and dreams were cut short. Some victims will never have the opportunity to realize their dreams.

These are the names and stories of just some of the 309 people who are shot in America daily, and the 93 who end up dying. The United States has protected the rights of gun owners, but at the cost of thousands of lives every year. The accepted status quo leaves blood on our hands.

The standard narrative of gun violence is that there will be casualties, but any restrictions on gun rights will result in more guns in the hands of criminals. This logic is hinged on the assumption that regulations will only affect law abiding citizens, and people committing crimes will still have free access to firearms. It may seem like a sound conclusion, but upon closer inspection, this narrative crumbles.

A plethora of inconsistencies in how Federal Firearm Licensees, or gun shops, are regulated allow for thousands of guns to fall into the wrong hands directly from gun shops. These holes in the law can be patched with full enforcement of current gun laws and additional common sense regulations. The law currently statesthat all Federal Firearm Licensees have to run background checks on anyone prior to purchasing a firearm.

Background checks performed by the National Instant Criminal Background Check System (NICS) have two major faults. Imperfect data entry into the NICS allows for people, who otherwise would be ineligible to buy guns due to a criminal history, to slip through the cracks. This flaw in the system can have catastrophic consequences, such as Dylan Roof killing nine people in a historically African-American church in Charleston, South Carolina with a gun he should not have been able to buy because he was charged with a misdemeanor in February 2015.

The second failure of the NICS is that it has too few criteria that would make a purchaser ineligible to buy a gun. Creating additional criteria for the NICS, such as restricting gun sales to people in treatment for mental illness, might have prevented the shooting by Aaron Alexis, who killed 12 people in September of 2013. A month before the shooting, he twice sought treatment from the Department of Veteran Affairs.

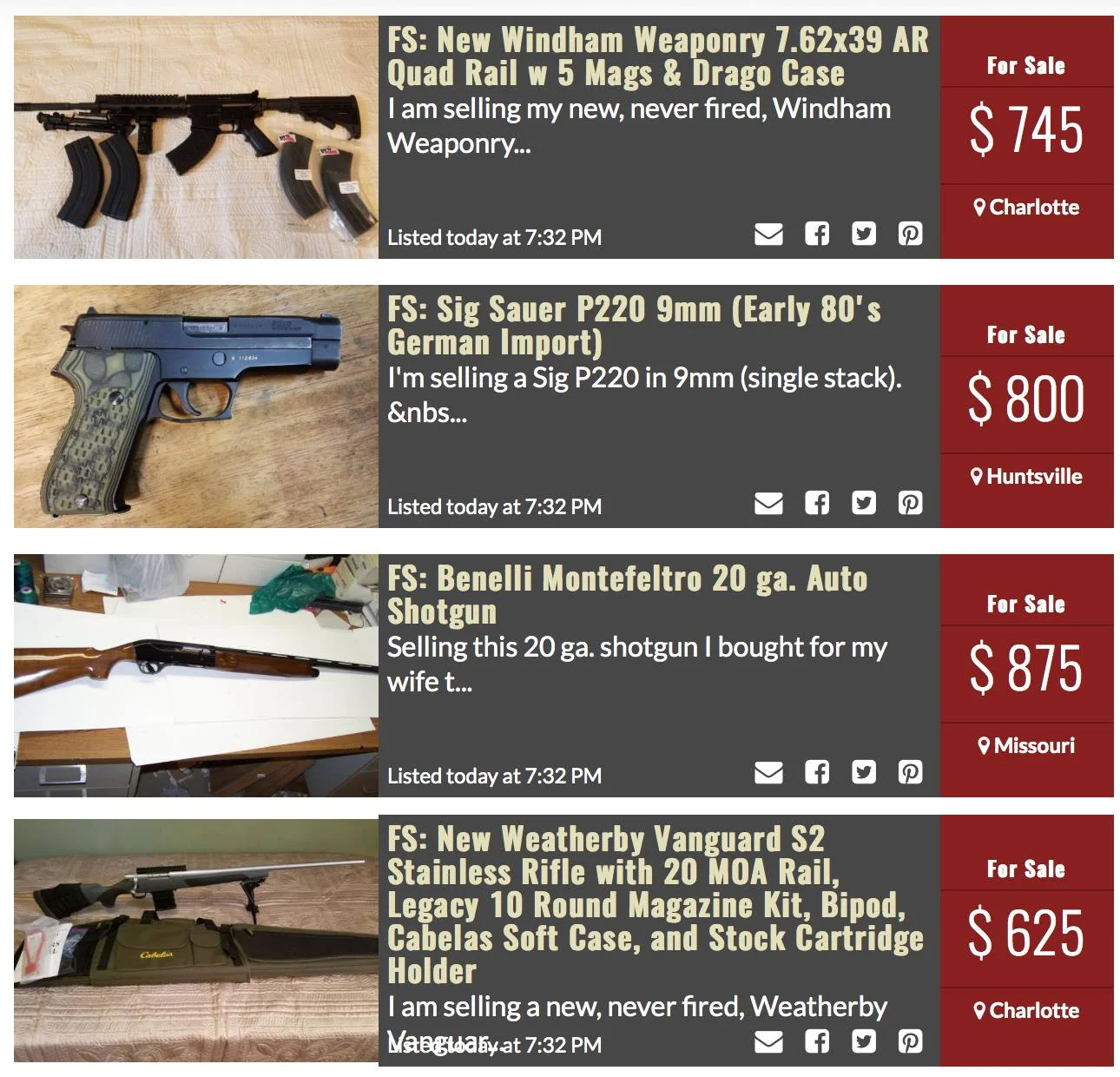

While using the NICS and buying from Federal Firearm Licensees is a flawed system, transactions in the secondhand market have even less regulation. Colloquially, buying through the secondhand market is referred to as the “gun show loophole,” but it encompasses more than just gun shows. Guns are also purchased via sites like Craigslist and Facebook, and are often gifted. All of those avenues are partially or completely unregulated. At guns shows, only Federal Firearm Licensees are required to perform a background check on buyers, and anywhere from 25-50% of vendors may not be licensed. Harvard researchers found that in practice, 15% of adults could purchase guns without a background check, which nationwide totals to approximately 5 million guns annually.

Gun shop owners are not all saints trying to grapple with an imperfect government database. The most frequent way guns enter the black market is they are bought from gun shops through straw purchases. A straw purchase is “when someone who may not legally acquire a firearm, or who wants to do so anonymously, has a companion buy it on their behalf.” In Dan Noyes’ piece, “How Criminals Get Guns,” he goes on to further point out the problems with Federal Firearm Licensees by stating, “many straw purchases are conducted in an openly ‘suggestive’ manner where two people walk into a gun store, one selects a firearm, and then the other uses identification for the purchase and pays for the gun. Or, several underage people walk into a store and an adult with them makes the purchase.” Many gun shop owners might be able to claim that they didn’t know the firearm would be given to someone else, and prosecutors have a difficult time to claim otherwise.

To combat the hurdle of deniability, in 2006, private investigators from New York City went to gun dealers in 5 states and caught 15 shops making illegal sales. Guns from those shops have been linked to over 500 crimes in New York City between 1994 to 2001. New York City plans to bring lawsuits seeking monetary damages from these guns shops. Other cities, such as Detroit and Chicago, have taken similar measures, but the challenge with this strategy is that it is done after crimes have already been committed. It also requires a large investment from cities, and it is difficult to narrow down which gun shops are the bad actors.

While straw purchases are a serious problem and some gun shops are bad actors, the general relationship between gun shops and crime is sometimes more complicated. Often, guns have traveled long distances and passed through multiple owners before being used in a crime. The average timeframe for a gun from the time of purchase to involvement in a crime is 13 years, and 80% of of guns come from out of state, making them especially hard to trace. The reason for this complicated relationship of time and place is gun traffickers take advantage of lax guns laws in states like Georgia and Florida and traffick them to cities like New York City and Chicago, where they will command the highest prices on the black market. This creates a problem for urban centers because they are impacted by lax gun laws in places outside their direct jurisdiction. Chicago has significant gun trafficking problems because it is easy to drive into Indiana in less than an hour, a state that has fewer gun laws. Even though there are strict regulations on gun shops in Chicago, the city’s laws mean little in practice because of trafficking.

The most substantial challenge to keeping guns in the right hands is the mobility of guns. New technological advances have offered one possible solution, which is to make guns owner specific. Commonly referred to as a “smart gun,” these weapons are only meant to fire in the hands of their rightful owner, which can be accomplished through a variety of methods. Early versions of smart guns required a ring with a magnet inside to unlock the trigger, which was to be worn by the owner. Newer models use a RFID-enabled watch that must be within 10 inches of the gun to work. Most recently, several companies are developing a system that will “measure the biometric data below a user’s skin in order to determine whether the individual holding the gun is the rightful owner of the weapon.”

These technological advancements are the most promising because smart guns with rings or RFID readers are truly non-transferable. Biometric or fingerprint readers could also help hold gun shop owners accountable for allowing straw purchases by making them calibrate the gun in store to the owner. This technology might have prevented the Sandy Hook school shooting from happening. Shooter Adam Lanza obtained a Bushmaster XM-15 rifle and a 0.22 caliber Savage Mark II from his mother’s collection, and then went on to shoot his mother and 26 other people, mostly children, at Sandy Hook Elementary School on December 14, 2012. Since the guns he used belonged to his mother, they would’ve been rendered useless if the guns used either biometric or fingerprint readers.

Despite its many benefits, smart guns are still widely unavailable in the United States because of how new the technology is and the resulting pushback from a mistrust of still developing technology. While older ideas of the smart gun date back prior to the 1990s, large gun manufacturers quickly learned to distance themselves from smart guns. Colton and Smith & Wesson were almost bankrupted by boycotts from gun rights activists after supporting smart gun development during the 1990s. Additionally, any gun shop owners who wanted to bring into their stores smart guns manufactured outside the United States have faced boycotts and, in some instances, death threats.

Market forces also play a significant role in the absence of smart guns. Alina Sleyukh, who writes for NPR, best explains this anomaly when she states that “[there is] a stalemated kind of supply-demand: manufacturers best positioned to make and market these new guns don’t want to go all-in on the idea without a reassurance of big orders, while no big buyer would put in such an order for an unestablished technology.”

A potential solution gun safety activists have pushed for is law enforcement around the purchase of smart guns, which would serve to incentivize companies to produce smart guns and build public confidence in the technology. Law enforcement can be assured that no other person could take their gun and fire it. Implementing smart guns in police departments can be done in a similar fashion to how police body cameras were implemented. Federal and state governments could offer incentives, such as provide funding for police departments that want to utilize the new technology. In 2015, the Justice Department provided $23 million in grants to 32 states for body cameras. The government has the potential to lead an industry toward safer practices by using their purchasing power to open up the market to consumers.

Besides obstacles in the market, smart guns continue to be unavailable because of significant backlash from gun activists. Opponents of smart guns say that they are unsafe because the underlying technology is unreliable. The common suggestion instead is to enforce current gun laws before creating new legislation. According to Wayne LaPierre, executive vice president of the NRA: “Obama could take every criminal with a gun […] off the streets tomorrow.” This narrative suggests that gun safety advocates are more interested in reducing gun ownership, and are choosing not to reduce gun violence through the existing legal channels.

Implementing smart guns in police departments can be done in a similar fashion to how police body cameras were implemented.

If properly enforced, the existing gun laws would allow fewer guns to flow into the black market. Unfortunately, those same gun rights activists who claim the federal government should enforce existing laws have made it nearly impossible to do so. They accomplished this by cutting the number of agents and funding at the federal agency, The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives, or ATF, which regulates Federal Firearm Licensees.

They have also written into law measures that inhibit the ATF’s ability to enforce the law. The most significant legislation that deters ATF from enforcing the law is the Tihart Amendments, which include provisions that prohibit ATF from releasing gun tracking information for cities, researchers, or prosecutors to use; require the FBI to destroy all gun purchaser background check information within 24 hours; and bar ATF from requiring gun shops to submit their inventory to law enforcement. All of these provisions make it difficult for the AFT to do their job. These restrictions are not a mistake which legislators who advocate for gun rights are eager to fix. In 2015, House Representative Charles Rangel from New York submitted a bill to the House called “the Enforce Existing Gun Laws Act,” which would repeal the Tihart Amendments as well as introduce other common sense reforms. The bill has 27 cosponsors, and not a single one of them are Republican. Since being referred to the House Judiciary Committee in June of 2015, it has made no forward progress.

Our gun culture is all encompassing. Almost anyone can buy a gun along with their groceries in a Walmart. Any movement toward a safer America where fewer people die from gun violence every year is seen as an attack on the liberties of gun-owning Americans. There is no silver bullet to end all gun violence, but instead, many smaller steps we could take to keep Americans safe. We have reached a painful stalemate, where little is accomplished and more blood is spilled. Smart guns are just one way to stem the violence, but even they still hang in the balance of uncertainty. The standard narrative so many Americans have bought into only serves to perpetuate tragedies. It is only until we decide that the death, the violence, and the blood are unacceptable, that we will move forward.

By Erika Smithson

Erika Smithson is a Public Affairs major with a minor in Political Science. This paper was written for COM 3040: Information and Society, taught by Professor Lisa Ellis. It is an examination on how developing technology will affect the current gun market and political landscape.