Woman Like a Man: Blurring Gender Lines

Societal pressures have always forced women to live in strict establishments where they are reduced to being a wife, sister, mother, or daughter. Bearing these roles, women in society have been binded into the duties that come with these titles. They are not allowed to engage in roles that are typically associated with men. Women are stuck doing what is considered to be feminine and what society expects of them. In Ana Castillo’s eyes during the 1970s to 1980s, women lived under the hegemony where men are supreme rulers and women are slaves with no hope of joining the high-caste society men live in, which led her to write a book of selected poems that was dedicated to the daughters of Latino men. Castillo could be considered an angry feminist, and justifiably so — her poetry champions that women should be equal to men and should not have to live by predetermined guidelines. In Daddy with Chesterfields in a Rolled Up Sleeve, Castillo portrays through her own personal experience that the archaic method of labeling specific practices as masculine or feminine has shoved women into categories of what they can and cannot do. Castillo emphasizes that this mentality should be purged by sharing situations where she felt oppressed in her life. Masculinity is not only for men — women can use it to empower themselves.

In the first two stanzas, Castillo shows a stark contrast between the roles of women and men in society. She says: “a man claiming to be/ my father/ was in her office.” The tone is mysterious, making the reader wonder if the man in the office is her father, and the word “claiming” gives a sense that the father isn’t a part of her life. Castillo also points out that “Mami was/ on her way (it must be serious/ I thought, Mami never misses work),” implying that both parents do not play an active role in the author’s life. However, the cause of this absence is for different reasons. Castillo specifically adds important information about her mother and italicized Mami to highlight that she is a hard worker. Mami is such a hard worker that she hardly has time to see her daughter, much less miss even an hour of work unless it was for a serious situation. Yet, there is no explanation on the father’s part. He just appears and the reader has no clue where he was, what he was doing, or if he even has a job. This contrasts with how Mami has to adhere to certain responsibilities and that she isn’t allowed to break out of the role of caregiver. On the other hand, Castillo’s father is free to do whatever he wants without having to care about how Castillo is affected by his absence.

This freedom that Castillo’s father has is very appealing. The author portrays the father as a suave man who “smokes cigarettes/ doesn’t ask permission, speaks English/ with a crooked smile: charm personified.” There is a tone of admiration for men who exhibit this charismatic persona. The author doesn’t express desire for the man himself, but for what he can do. As a child, Castillo is fascinated by the male figures in her life, even though her father just “hangs out with the boys” while their wives “work the assembly line.” There is no sign that the father, or the men he hangs out with, do anything productive, but their images are idolized. Castillo admires the life that is available to these men; they are allowed to forge their own path. They can decide to provide for their family or not without being punished.

There is a double standard when a woman tries to take on the traits that traditionally belong to men. Castillo compares herself to her sister, Anita. Castillo “Learns English in school…/ gives flowers to the Virgin every spring” while Anita only knows “yerba buena, yerba santa, epazote.” Castillo tries to take on masculine roles by learning English, which was something that only men learned, while her sister learns how to cook and take care of her family using various plants. Castillo didn’t want to learn about different plants to make into tea — she wanted to be educated. Unfortunately, these traits don’t make Castillo desirable or appreciated, like men are. Instead, her mother scolds her for being like her father: “a dreamer/ think someday you’ll be rich and famous.” By doing this, Mami tries to take away Castillo’s sense of agency. Mami, who is trapped in the role of femininity, is trying to make her own daughter conform to the societal pressures of cooking, cleaning, and caring for men. Castillo is depicting through the voice of her mother that women also perpetuate the misogyny directed at them. As a woman, Castillo is not given the chance to have the freedom her father does. Her father speaks English and dreams about things that may never happen, but he was never scolded for doing so. In today’s society, women are still discouraged from following their aspirations. There is a lower quantity of women in the United States who pursue a career in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) due to the fact of the gender bias that still exists. A study done in 2014 concluded that men and women would rather hire a man for a job that included math because women are considered less knowledgeable in these areas, after having to prove themselves over and over.

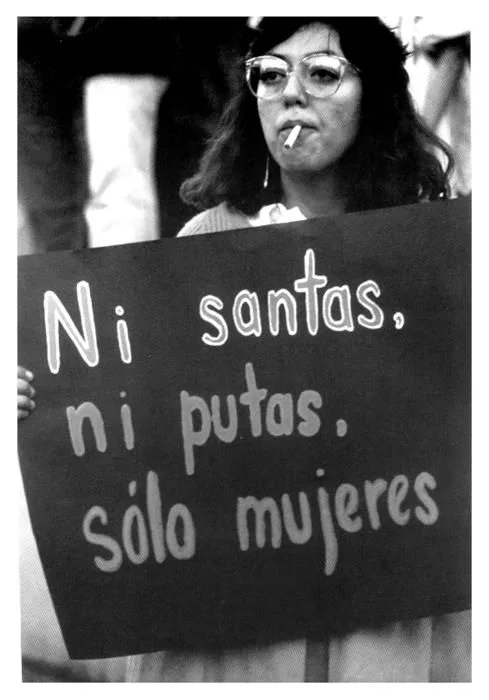

Being in a dress doesn’t stop Castillo from smoking or drinking. What stopped her in the past was society’s unspoken rule that men can do things that women can’t.

As an older woman, Castillo fights against gender bias and becomes the image of a woman who is independent — a woman who is able to be masculine. The narrator states, “I speak English with a crooked smile/ say “man,” smoke cigarettes/ drink tequila.” Castillo now embodies the qualities she so admired from her father, but doesn’t believe her actions to be masculine. The quotations around the word “man” emphasize Castillo’s belief that doing these masculine things is not only for men. Rather, she performs these actions because she can. According to Mami, women weren’t allowed the liberties of an easy life. However, Castillo takes a route that no woman dared to cross — she begins to act like a man. In the same stanza, Castillo contrasts masculinity by describing her feminine qualities through her looks: “the silk dress accentuating breasts.” Being in a dress doesn’t stop Castillo from smoking or drinking. What stopped her in the past was society’s unspoken rule that men can do things that women can’t. This line also reminds the reader that Castillo taking on these characteristics doesn’t make her a man. Today, it is still difficult to dilute the line between men and women. If a woman dresses in men’s clothing because she is more comfortable that way, society sees her as a man and avoids the fact that she is still a woman. Castillo specifically points out the dress to express that although she is partaking in activities that are associated with men, she is still a woman and can do as she pleases as a woman without care of judgement.

Free to do as she wants, Castillo tries to push this ideal onto other women. Castillo shows them that as a woman, she can take on roles that men have, that she can be the suave person who doesn’t ask for permission. This doesn’t make her masculine or a man, but a person who has freedom over her own life. The author states, “because of the seductive aroma of mole/ in my kitchen, and the mysterious preparation/ of herbs, women tolerate my cigarette.” The word “my” has an assertive tone, with the lines before describing the home as seductive with the preparation of herbs, which was characterized as a feminine duty earlier in the piece. It is possible that women tolerated her smoking because they realize that they can also take on roles belonging to men. Castillo demonstrates that she can handle taking care of the home as well as being a dreamer and having the freedom to do as she sees fit. Maybe that’s why it would seem so “seductive” for the women to see Castillo in this state.

Castillo concludes the piece with a powerful last line: “you got a woman for a son.” She says this to her father, who never paid attention to her because she was not the kind of women he looked at. He seemed to see women only as objects for his dirty work. This last line adds dry humor to the fact that her father never noticed her as a woman, but only paid attention when she took on these masculine traits. By telling her father that he “got a woman for a son,” Castillo takes the concept of masculinity and twists it in her favor, almost boastfully, as if she is shoving this in the father’s face. She is able to do everything a son could do, but as a woman. Castillo proves that the notion that masculinity is purely for men is outdated by showing that women can smoke, can drink, and can hang out just like the guys.

Ana Castillo made it her mission in Daddy with Chesterfields in a Rolled Up Sleeve to subvert the predefined roles of women and men in society. Through her own struggle to break away from societal pressures, Castillo creates a path for women to see that they, too, don’t have to be stuck in feminine roles. By expressing this, she redefines masculinity. Women do not have to live under man-made rules that exclude them from doing the same as men. In Castillo’s world, women can do whatever they please. They always had the right.

By Ashley Somwaru

Ashley Somwaru is a senior and a RefractMag editor. When she’s not drowning in her love for poetry or going down the rabbit hole of funny Youtube videos, she enjoys immersing herself in controversial stories.