"Degenerate Art": art's fight against Nazism

On July 18th, 1937, the National Socialist party celebrated the glorious nation of Germany the only way any self-respecting fascist totalitarian state should: by opening an art exhibition. Wasting no expense, Reich Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels commissioned an entire art museum built especially for this momentous occasion. The Great German Art Exhibition was to overwhelm the public with awe for Führer Adolf Hitler’s absolute power. This would symbolize the end of an era of corruption and disgrace, brought on by the dangerous foreign ideas responsible for the fall of Germany after World War I.

Nazi Germany had to cleanse itself of the art embodying these ideas. Goebbels’ Reich Chamber of Culture went to the extreme effort of confiscating thousands of works of modern art within Expressionism, Surrealism, Cubism, Futurism, and Dadaism; all painted as too intellectual, Communist, and consequently, too degenerate. How did they decide to distort this cultural life that did not support Nazi ideology? By opening another art exhibition.

Given the title, Entartete Kunst, or Degenerate Art, the exhibition was held in the dark, narrow halls of the Institute of Archaeology. The Reich Chamber of Culture appointed painter Adolf Ziegler to organize 650 of the confiscated paintings and sculptures for the sole purpose of condemnation.

This worked, possibly all too well. Over a period of only a few months, more than two million people crammed themselves into the exhibition. Nearly five times more people went to go see Degenerate Art than the great German art, and for those people, the Nazis not only created an opportunity for discourse about modern art, but they deemed it worthy of discussion.

The Nazis were acknowledging just how powerful art was as a political tool. They didn’t eradicate the avant-garde with censorship — they legitimized it.

When painter Ernst Ludwig Kirchner met fellow architecture student Karl Schmidt-Rottluff in 1905, he wrote, “I saw the same light [of determination] shining in Schmidt-Rottluff’s eyes, when he came to us, looking, like me, for freedom in free work… the free drawing from the free human body in the freedom of nature.” Bonding over a mutual desire to paint with freedom, the painters founded the revolutionary German Expressionist group Die Brücke, The Bridge, between the past and the present. Their art aspired to convey the personal experience of pure emotion through vivid colors and violent and sexually charged imagery. It was precisely this subjective perspective that the Nazis despised. After all, as the government increasingly stressed the collective, utmost devotion to Germany, art dedicated to extreme emotion inevitably meant social critique.

Otto Dix’s War Cripples (45% Fit for Service) (1920), depicts a parade of mutilated veterans from World War I that are still deemed fit for service by the military. Dix, disillusioned by the idea of dying for one’s country after fighting in battle himself, sought to show the reality of war in these cartoon-like figures. When displayed at Entartete Kunst, it was captioned “Slander Against the German Heroes of the World War.”

Otto Dix – War Cripples (45% Fit for Service) (1920) – Source

So what exactly made the Germans so suspicious of internationalism? It most likely had to do with the $33 billion U.S. dollars Germany was forced to pay as a part of 1919’s Treaty of Versailles. For those of you trying to visualize this money, because money is a concept after all, Germany had just finished paying these WWI war reparations on Oct 3rd, 2010. Furthermore, reemergence of the pseudo-scientific field of eugenics sought scapegoats and the avant-garde increasingly became associated with the elitist French and Communist Jews. German art associations were soon founded for the purposes of reviving German Romanticism and attacking artists and museum directors who displayed modern art. The National Socialist party was ordering the removal of artworks by Ernst Barlach and Paul Klee from museums long before Hitler came to power, but when he did, annihilation of modern art became systematic.

Even designation of the word entartete, or degenerate, for modern art complemented the increasing persecution of the Jewish people. Degeneration implied racial and cultural inferiority, and moral depravity. Although marketed as pornographic and the “art of the mentally ill,” the ideology of modernism is simply the polar opposite of fascism. Fascism demands a highly regulated state — strength through unity — for the sake of national interest. Meanwhile, modern artists, writers, architects, philosophers, and other creatives were moving away from outdated traditions, suddenly conscious of themselves, their subjectivities, and their power to change the world around them. Wassily Kandinsky said he hoped his abstract paintings, such as the hypnotic, cosmic, and geometrically harmonious Several Circles (1926), would “help heal the crack in the inner soul of mankind.” Somehow, Entartete Kunsttwisted this and deemed his paintings barbaric.

Fascism sought to create a collective identity and to brainwash with patriotism, whereas modern art intended to inspire different introspections among individuals, particularly with ambiguous colors and forms.

Wassily Kandinsky – Several Circles (1926) – Source

To build his ideal Germany, Hitler stressed that true German art be national rather than international, permanent rather than fleeting, and elevating rather than critical. The subject matter “ha[d] to be popular and comprehensible… ha[d] to be heroic in line with the ideals of National Socialism… [and] ha[d] to declare its faith in the ideal of beauty of the Nordic and racially pure human being.” Therefore, the Nazi-sanctioned art at Grosse Deutsche Kunstasstellung was propaganda, using the idealized everyday life as an agent to instill Nazism.

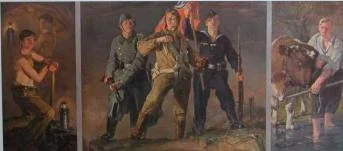

Unlike Dix’s War Cripples, Hans Schmitz-Wiedenbruck’s triptych Workers, Peasants, and Soldiers (1941) is the artistic equivalent of a shirtless firefighter calendar. No emaciated peasants or maimed soldiers here. Just strong heroes united in working hard and contributing to Germany.

Hans Schmitz-Wiedenbruck: Workers, Peasants, and Soldiers (1940) – Source

“They took the frames off of the paintings, hung them thematically in paradox, and gave meaning to what had previously been deemed “meaningless.” What they failed to realize is that the more they censored something, the more value they gave it.”

The National Socialist party tried desperately to mock and eventually destroy the modern art movement, but they still called it art. They took the frames off of the paintings, hung them thematically in paradox, and gave meaning to what had previously been deemed “meaningless.” What they failed to realize is that the more they censored something, the more value they gave it.

The once idealistic Kirchner committed suicide just a year after the exhibit, but it is his paintings that have survived to hang on the walls of museums. It’s his name we remember along with all the other modern artists who inspired so many art movements, encouraging experimentation.

Meanwhile, Nazi art was hidden away by the United States Department of Defense, generally deemed technical and conceptual failures by art historians.

By Sarah Park

Sarah Park is an English Major and Art History Minor at Baruch. She wrote “Degenerate Art” for ART 3040: Art & War with Professor Karen Shelby because censorship in the arts is despicable.

Cover picture: Entartete Kunst – Degenerate Art Exhibit – Source

1939 ART CENSORSHIP DEGENERATE ART GERMAN HITLERMODERNIST NAZI WWII