Yoshihiro Tatsumi's Critique of Anomie

With whimsical and fantastical storylines, the Japanese phenomena known as manga is loved for amusing children and providing an escape from the mundanity of adulthood. Meanwhile, manga has a darker, more brutally honest younger brother called gekiga, which seeks to ground readers in the harshness of reality and urban anomie. This style was pioneered by Yoshihiro Tatsumi in the 1960s during Japan’s high-growth economy, when droves of young people were moving from the countryside to work in urban factories. As an increase in the post-war population demanded an increase in mass production, alienation and the desensitized human condition soon became the cultural norm. Tatsumi’s Beloved Monkey is an implicit critique of this constraining established order in Japan that resonated precisely with the young working class and social dissidents. Tatsumi explores the dilemma of the modern man, the social mobility of women, and the substructure of a prosperous modern Japan, through acute use of symbolic imagery, subtle sound depictions, and brazen embrace of the grotesque.

Beloved Monkey’s unnamed protagonist is an anonymous factory worker, depicted as such to capture the universal condition of man. The comics spoke specifically to the disenfranchised laborers who dwelled in the underbelly of a rapidly modernizing society. These workers were the primary audience of Tatsumi’s gekigaserializations who, like the protagonist, left the rural countryside and moved to urban cities such as Tokyo, Osaka, and Nagoya as Japan emerged from Occupation and embarked on the post-war economic miracle. They often took whatever low-wage jobs were offered and lived in small, cramped apartments, which the protagonist ironically calls his “single-room castle.”

Yoshihiro Tatsumi – “Beloved Monkey.” Abandon the Old in Tokyo. Drawn and Quarterly, 2012: 87 – Source

The first impression Beloved Monkey seeks to evoke is of a bleak lifestyle that is claustrophobic, conceived in various cropped aspect-to-aspect transitional frames. The incessant industrial noises are portrayed through onomatopoeias. The factory worker, minuscule to the machinery, is surrounded by its clanging: “KTUNK KTUNK, KLANG KLANG.” Even the speech bubble of his co-worker is muffled with “KTUNK KTUNK,” as the factory worker thinks, “It’s too loud to talk, so there’s no need for conversation,” and “The noise of machines overtakes the world as everyone becomes isolated.” Tatsumi depicts multiple perspectives of the disenchanted protagonist as he maneuvers through the concrete cityscape. This technique was influenced by the use of dramatic effect in film. He muses while being swallowed in a crowd of people, “The more people flock together, the more alienated they become.” The motif of the individual within the crowd emphasizes the isolation of man in modern society; the people themselves behave like automatons accustomed to fulfilling a daily routine, completely dissociated from each other. In a frame crammed with people, the eerie lack of sound effects captures the pronounced sense of the loneliness of urban living. He ascends and descends a pedestrian bridge in solitude above heavy traffic congestion, huffing and puffing in Sisyphean exhaustion.

It is only when the factory worker arrives home to his “single-room castle” that he puts on his favorite record, comforted by the human voice singing. Ironically, the music is created by the mass production of records and record players, and the protagonist is only given an illusion of feeling human connection. Even in this brief interlude into the sanctuary of his humble abode, the cracked window shows ominous landlines and power plants rising over the roofs of traditional Japanese houses. The next panel only has the interjection “KABOOM,” which startles the factory worker awake. The deafening roar of construction traps the protagonist between layers of reverberation, suggesting one cannot escape the intrusion of modernization. From a bird’s eye view, he is later shown being swept up and squished into a train by a mass of commuters, losing his identity in the crowd. In the central frame, the readers are looking at the back of heads moving towards the screeching train from the protagonist’s point of view. As a product of industry and a symbol of modernity and masculinity, the train alludes to Edelman’s theory of Reproductive Futurism — the continued process to produce and authenticate the new modern social order.

This phallic Futurist symbol is appropriate, in relation to his encounters with a woman named Reiko, whom he meets at the zoo. Reiko is an active female character, representing the new post-war class of independent working women as an employee in a hostess bar. While the factory worker rarely speaks, it is the woman who carries the conversation and takes an unconventional and assertive role, offering an invitation to call. She is decidedly a realist and opportunist in an era where gender roles have shifted and women must start to support themselves. In contrast, the protagonist is filled with fanciful hope and not only replaces his pornographic nude pin-up with his fantasy of a real woman, but also irrationally decides to resign from the factory. After losing his left arm in an accident, and being without a job, the protagonist goes to seek comfort from Reiko. It is then revealed that she had only been interested in him for his financial stability.He is rendered impotent and immobile in a rapidly changing city, unable to make meaningful human contact or find work.

The most striking part of this gekiga is not the realist narrative of an industrial compound, but the curiously surreal side plot of the factory worker’s pet monkey. The monkey always has his back to the protagonist, dressed in a polka-dotted shirt, hunched over next to a television packaging box and a tin of tea. The worker states that “the only time [he] feels human is when [he’s] with [his] monkey,” the monkey perhaps reaffirming the worker as the dominating presence in the shared space. However, Tatsumi seems to suggest that the circumstances of people are beneath animals and the automation of mankind’s passivity and regimented lifestyle has ultimately compromised humanness. A train passenger comments, “We’re packed in here like sardines while the cows are traveling like kings.” The protagonist goes to the zoo thinking, “It almost feels like the animals were here to watch humans.” The zoo animals are kept in captivity, but their artificial environment is actually parallel to the man-made concrete cityscape. Tatsumi emphasizes this shifting hierarchy of human value by depicting an advertisement for a 3 million yen dog in stark contrast to the 300,000 yen the protagonist received as part of his worker’s compensation money.

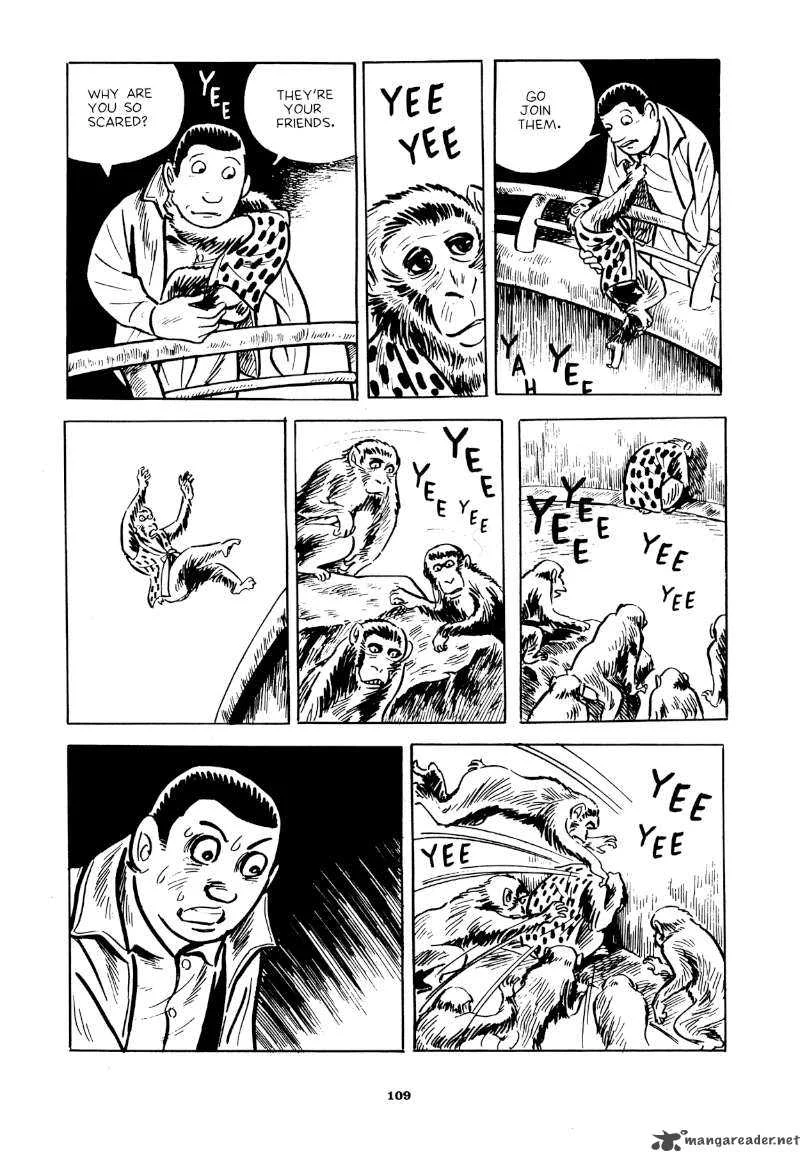

Yoshihiro Tatsumi – “Beloved Monkey.” Abandon the Old in Tokyo. Drawn and Quarterly, 2012: 109 – Source

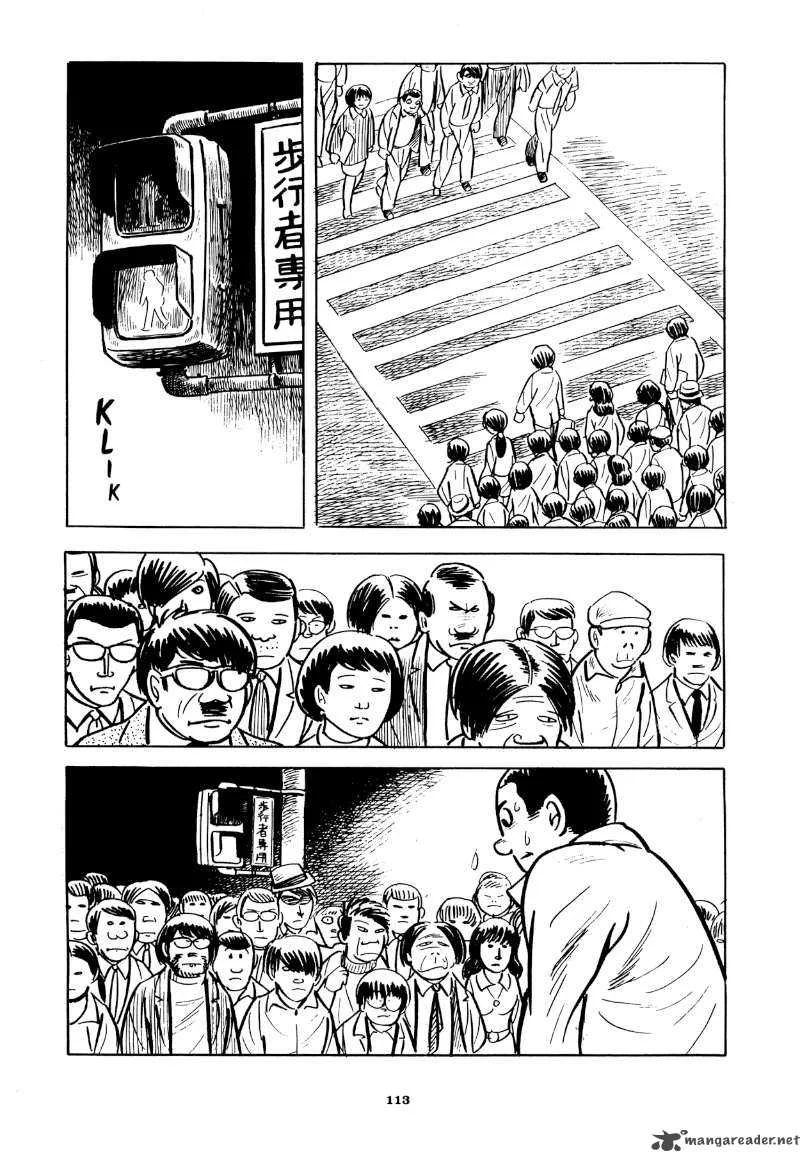

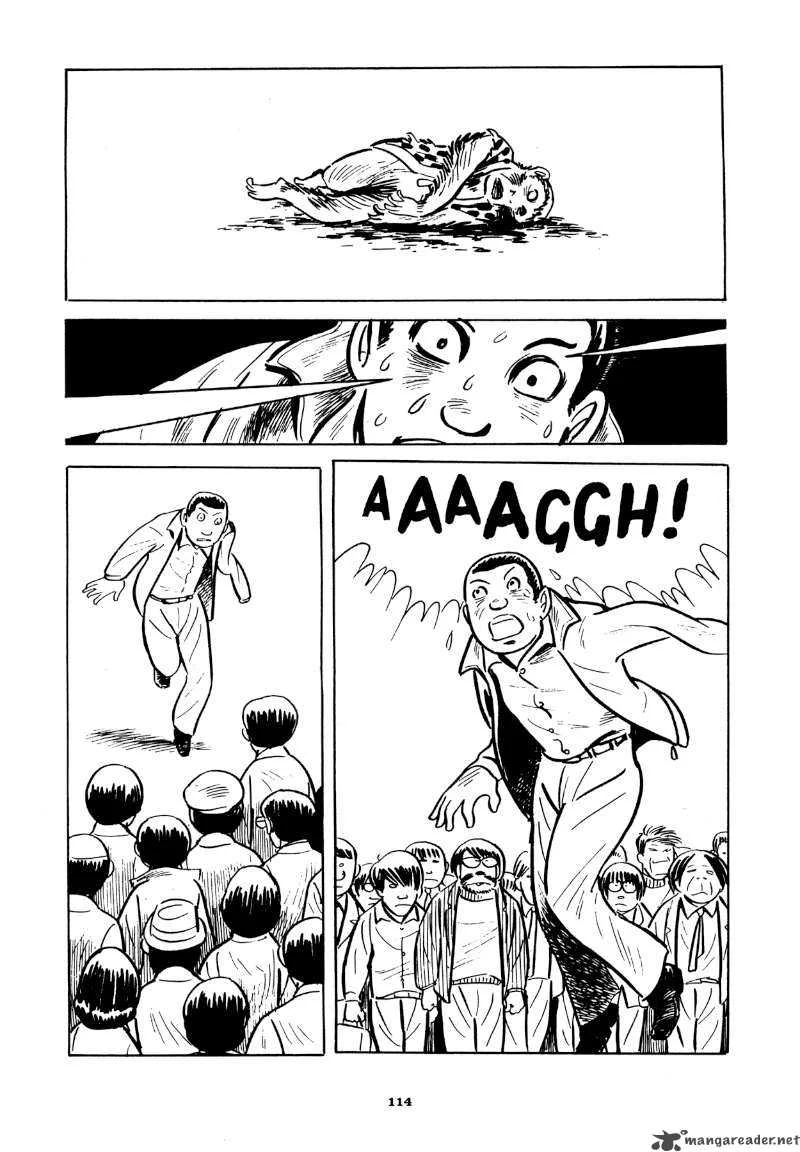

In one of the gruesome final scenes, the now-disabled and unemployed man returns his pet to the zoo, only for his beloved monkey to be torn apart by the mass of screaming wild primates. Whether it is because the zoo monkeys sensed the domesticated monkey was different from the polka-dotted shirt it wore, or that the new monkey was simply unwelcome, the scene reflects the savage consequences of being an individual. Meanwhile, the protagonist is rejected as a productive member of modern society because of his disability. Haunted by his beloved monkey’s corpse, the protagonist panics as he is about to cross a crowded street. The close-up panels of the traffic light, yet another innovation of modernity to denote safety to march forth, suddenly become daunting. Terrified by the threatening mass of strangers he was once a part of, the protagonist seems to imagine being brutalized like his monkey. He rejects blending into the crowd and runs away screaming.

Yoshihiro Tatsumi – “Beloved Monkey.” Abandon the Old in Tokyo. Drawn and Quarterly, 2012: 113 – Source

Yoshihiro Tatsumi – “Beloved Monkey.” Abandon the Old in Tokyo. Drawn and Quarterly, 2012: 114 – Source

As commentary on the status of the individual within societal constraints, Tatsumi Yoshihiro’s gekiga imparts a universal semblance that readers can connect with outside of Japan’s high-growth period. Yoshihiro’s artwork exposes the pervasiveness of urban anomie, scrutiny, and daily pressures to conform to society. His unnamed protagonists often meet unconventional, unresolved endings and are unable to reconcile the dynamisms of an altering world. Gekiga demands more freedom for an individual to maneuver in community and domestic spaces, ultimately questioning how much of our humanity we are willing to lose.

By Connie Huang

Connie Huang is majoring in Arts Administration and English Literature. She wrote this for the Critical Approaches to Japanese Pop Culture class with Professor Shigeru Suzuki.

Cover Picture: Yoshihiro Tatsumi’s “Beloved Monkey” – Source

ART COMMODIFICATION GEKIGA GRAPHIC NOVEL JAPANMANGA URBAN ANOMIE